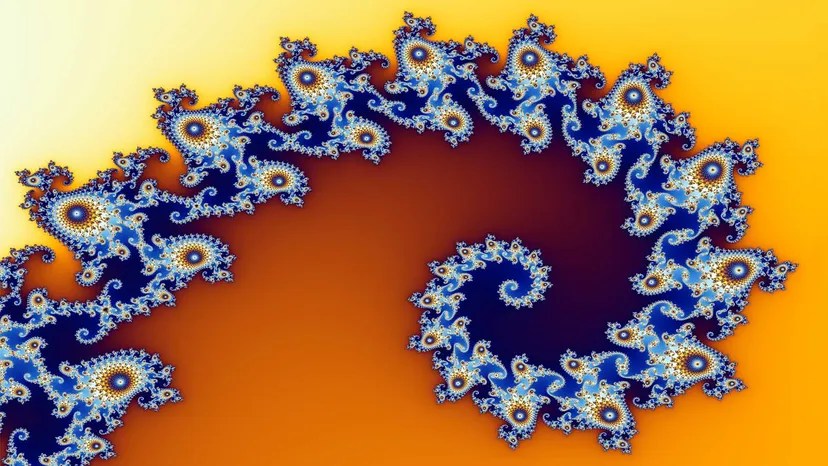

As Aldous Huxley writes from William Blake, “If the doors of perception were cleansed, everything would appear to man as it is, infinite” (Huxley 1). I think it is a great shame for Hamlet; for the doors of his perception are not cleansed but have etched on them the runes of fate and death, carved in by the self-reflective nature of tragedy. This raises the question: how can a genre be self-reflective; how is it possible for tragedy to be the subject of itself? I believe we can find an answer in Shakespeare’s Hamlet, in which tragedy is not a container for Hamlet to occur within; it is the story, the subject, and the protagonist. Through a recognisable pattern and repetition of themes emerges an aesthetic consciousness, that is, a self-reflective style through which tragedy becomes aware of itself. Think of tragedy as a cognitive descent; it seeps into Hamlet’s mind, subtle at first, then disorientating, slowing his movements, dissolving his sense of self until he is thinking entirely in tragedy. By focusing on recursion, we can liken tragedy’s repeating pattern to a fractal, spiralling through structure, into Hamlet’s perception, and ultimately embodying his sense of self. This essay will illustrate that tragedy is a form of consciousness that reveals itself through structure, Hamlet’s perception, his soliloquies, and his existential disintegration. To achieve this, I will focus on three central themes: tragedy and its structure, akin to a fractal; tragedy as expressed through its characters; and the collapse of Hamlet’s sense of self.

The Tragic Genre as a Fractal

Before I explore how tragedy is an aesthetically conscious genre, I want first to examine its structure, similar to a fractal, that enables it to reflect upon itself. However, let us begin with definitions for clarity: when I speak of consciousness, I do not mean conscious in the biological or sentient sense. Instead, I attribute consciousness to an aesthetic quality or a style that expresses consciousness by employing self-reflective devices. Therefore, being aesthetically conscious means that the genre is aware of its structure and themes, leaving it able to comment on its form and meaning. Secondly, a fractal is a geometric pattern that infinitely repeats itself on multiple scales, each part possessing smaller pieces that resemble the whole (Liebovitch and Shehadeh 191). I am using a fractal as a metaphorical insight into tragedy because it aligns with the literary idea of mise en abyme, “an illusion of infinite regress […] by a writer or painter incorporating within his work a work that duplicates in miniature the larger structure, setting up an unending series” (Snow 3). The important point for us is that, while the fractal may evolve, or branch out in new directions, it remains recognisable and patterned. It is here that tragedy and fractals share a key similarity: they both achieve a self-repeating structure, resulting in a patterned and recognisable form. Fractals achieve this across scales of form, and tragedy across layers of meaning and thematic conventions.

For example, works such as Oedipus Rex, Hamlet, and modern productions like Death of a Salesman express tragedy as a repeating, recognisable pattern. Authors may reshape and reinterpret the surface, but beneath the core remains a recognisable pattern. Tragedy as a genre functions with recognisable structures, themes, and characters that persist across time. George Steiner writes, “tragic drama arises out of blind necessity and that man’s encounter with it shatters him […] the spheres of reason, order, and justice are terribly limited” (Steiner 5). Essentially, the tragic protagonist faces an inner flaw or other forces beyond their control, such as fate, God, or death, which ultimately destroy them. Additionally, tragedy often unfolds in worlds where logic or morality cannot save the characters, even if the protagonists are morally upright or rational. Due to these recognisable patterns, tragedy resembles a fractal as it repeats, but it does so while spiralling up and outward into new domains and adaptations. In this way, the patterned and recognisable structure of tragedy, by constantly re-enacting its form across different works, becomes a medium that reflects on itself, an aesthetic that is conscious of its form. Ultimately, tragedy is thereby a genre that not only tells a story but reflects on its form in the telling, becoming the subject of itself.

Aesthetic Consciousness at Work

Building on the idea of the fractal nature of tragedy, I want to outline an example of aesthetic consciousness. Specifically, how tragedy can represent and comment on its conventions and themes, as best seen in Hamlet. As I have mentioned, I define consciousness, for the sake of this essay, as an aesthetic quality. Simply put, tragedy is conscious because it has a self-reflective aesthetic; or, according to George Barrett, tragedy is a play in dialogue with itself about what it means to be a tragedy (Barrett 349-350). Now, enter Hamlet, a quintessential example of a tragedy as aesthetically conscious and the subject of itself. Hamlet is not just an instance of tragedy; it is part of a larger repetition that reveals the self-aware pattern of tragedy. In particular, The Murder of Gonzago that Hamlet renames The Mousetrap play, when Hamlet and his family share the role of the audience: “Madam, how you like this play?”, to which Gertrude responds, “The Lady doth protest too much, methinks” (Shakespeare 3.2.253-254).

While watching The Mousetrap play, these characters are not only spectators of the play but also unwilling participants in the crime it is trying to reveal. However, as you read The Mousetrap, you enter yet another play, creating metatheatre, or a play-within-a-play. This is what Lionel Abel defined as “theatre pieces about life seen as already theatricalised” (Abel 60). Essentially, characters appearing within the play “are not simply caught by the playwright in dramatic postures […] but because they knew they were dramatic before the playwright took note of them […] they are aware of their theatricality” (Abel 60). This scene brings with it the conscious aesthetic idea, an intense rising awareness, in which Hamlet is not only participating in his tragedy but is writing, directing, and producing another one. Hamlet makes this clear before it begins, “The Mousetrap. Marry, how? Tropically. This play is the image of a murder done in Vienna… ’Tis a knavish piece of work” (Shakespeare 3.2.261-265). In this moment, Hamlet is not just attempting to expose Claudius’s guilt; he is exercising the conventions of tragedy itself within his tragedy. This doubling is tragedy seeing its reflection; a commentary on how tragedy works. Therefore, it is no longer just about the plot, but the tragedy is thematizing its mechanics, becoming its subject.

Moreover, it is here that the conscious aesthetic comes to the forefront, akin to metacognition or thinking about one’s thoughts; tragedy is not just happening, it is watching itself happen and commenting on itself. Similar to a fractal, Hamlet’s Mousetrap play is a miniature fragment of the wider tragic genre, but as you spiral outward, you realise The Mousetrap is nestled in Hamlet’s larger tragedy. This calls back to the idea of mise en abyme, Shakespeare is incorporating in his own play an additional play that repeats in smaller size the larger conventions of tragedy, inducing the patterned spiral. This, in turn, reflects the greater tragic pattern it both imitates and perpetuates. Overall, tragedy is not just something happening in the background of Hamlet, driving the plot; it is something that is concerned with itself. From within the recursive pattern of Hamlet, tragedy rises not just as a plot, but as a genre commenting on its form; it is aesthetically conscious and pays close attention to the subject itself.

Spiralling From Structure Downward into Character

After exploring how tragedy can be the subject of itself through an aesthetically conscious structure, I will now spiral further downward from structure into character. In this section, I will illustrate how Hamlet himself becomes an instrument of tragedy, how the genre infiltrates his mind, memory, perceptions and actions, and ultimately leads to his undoing. As we have seen, tragedy, much like a fractal, repeats itself on multiple levels. Specifically, just as tragedy reflects on itself through structure, it does as well within Hamlet’s psyche. To show this, we can look for tragedy’s recognisable signs and patterns etched into Hamlet’s perception and thoughts. One of the earliest moments is the initial act of Hamlet and his encounter with the ghost of his father when tragedy begins to inscribe its conventions into his consciousness. An instant recognition is when Hamlet cries: “O my prophetic soul! My uncle!” (Shakespeare 1.5.40). This encounter is not just the motivation for Hamlet; it is tragedy infiltrating his consciousness. Just as a fractal repeats its pattern at smaller and smaller scales, tragedy has embedded itself not just in structure, but now in Hamlet’s perception, so that he starts thinking in tragedy.

As Natoli puts it, Hamlet’s “own distinct human life, body and consciousness, becomes divided” (Natoli 94). Tragedy is not a force happening to Hamlet as if only directed by structure; it is repeating its themes within Hamlet’s consciousness. Hamlet begins to internalise tragedy and its patterns; he starts thinking in terms of revenge, downfall, doubt, and obsession. In a sense, this could be Hamlet’s psychological transformation, tragedy begins to structure his perception. As Natoli writes, “the ghost finds a place in Hamlet’s ‘mind’s eye’” because it emerges not only from the plot but from “the desires and fears of the past” (Natoli 94). Tragedy is no longer an external feature of the world Hamlet inhabits, it is his consciousness, and it shapes his memory of the past and his perception of the present. For instance, think back to when Hamlet’s father first asks, “Remember me?” (Shakespeare 1.5.95-100). This plea by his father is not only a call to memory, but also the beginning of Hamlet internalising the tragic pattern of revenge. Once Hamlet submits to his father’s request of carrying out his revenge, Hamlet announces “And thy commandment all alone shall live Within the book and volume of my brain” (Shakespeare 1.5.92–104). From this point on, Hamlet is not haunted by a ghost, but by the weight of the past and what it demands of him. The past returns into the present and shapes the future, it moulds how he thinks about and perceives the world.

Interestingly, this is not unlike Oedipus Rex, where Oedipus is driven to resolve his true identity, only to realise he has already fulfilled a prophecy of which he is unaware. While Hamlet is asked to remember the past, Oedipus first denies it and must uncover it. However, for both, tragedy does not remain external, it enters their mind, that is, they begin to think in the tragic pattern. Fundamentally, what starts as a structural force that tragedy can execute within, eventually tragedy is internalised. Therefore, tragedy’s aesthetic consciousness, the genre’s self-reflective form, shapes both the structure and the psyches of the characters, shaping their actions, thoughts, and perceptions.

Spiralling Past Character into the Identity of Tragedy – Hamlet Losing Himself to Tragedy

In this final section, I hope to illustrate the deeper levels of recursion: past structure and character, into being itself. I will demonstrate how Hamlet’s most intense moments of introspection leave him not just as a protagonist but as a manifestation of tragedy’s awareness of being. Essentially, tragedy reaches a recursive density so intense, falling on Hamlet, that it takes over his sense of self. In this light, we see how tragedy, as a genre, perpetuates its recognisable pattern through the structure and minds of its characters, like a fractal, repeating itself at smaller and smaller scales. Furthermore, we know that through the repeating pattern tragedy becomes aware of what makes up that pattern, giving it an aesthetic consciousness, or where tragedy becomes the subject of itself. However, it is now time to approach the most intense concentration of the tragic pattern in Hamlet, a local singularity a part of the wider whole in the infinitely repeating fractal of tragedy. At this point, tragedy no longer surrounds Hamlet or is working to shape his psyche, but in one final possession wears him like a suit. Tragedy speaks through him, moves through him, until Hamlet beneath the fabric begins to fade away and tragedy takes over. To put it another way, Hamlet is no longer a prince, not a son, not even a man; he is a moment of tragic recursion so deep he speaks only in the voice of tragedy itself.

The rest of this section will focus on Hamlet’s soliloquy “To be or not to be” (Shakespeare 3.1.64-65), to show this idea of tragedy at its most intense recursion and self-awareness. After Hamlet’s psyche is moulded by tragedy and he delivers his “To be or not to be” soliloquy, his sense of self collapses under the weight of tragedy’s reflection. A useful author to support this idea is Friedrich Nietzsche and his Apollonian and Dionysian framework, borrowed from the Greeks, and discussed in The Birth of Tragedy. Fundamentally, the Apollonian force embodies order, reason, individuality, and structured form, whereas the Dionysian force represents chaos, emotion, collective experience, and the dissolution of boundaries. Nietzsche suggested that Greek tragedy arises from the tension and interplay between the Apollonian and Dionysian forces. Furthermore, Nietzsche went on to say that in intense moments of Dionysian experience, this framework can be elevated from an individual experience to a universal one. However, in the case of Hamlet and his “To be or not to be” soliloquy, I believe that his introspection is the scale between Apollonian and Dionysian forces tipping toward the Dionysian dissolution of the self, where Hamlet becomes less of an individual actor and more a vessel through which tragedy comes to take complete control. As Nietzsche writes, “Man is no longer an artist, he has become a work of art” (Nietzsche 24). In that moment, Hamlet loses his individuality and becomes the mouthpiece for tragedy to speak through. Tragedy as a fractal has reached its most dense point, it is aesthetically conscious not only through structure and character but now through being itself, through the disintegration of Hamlet’s own experience.

Although, just as we have reached the densest point of Hamlet, it was still a part of the wider tragic fractal spiralling beyond Hamlet into infinity. For us, it is time to zoom back out and make sense of the downward trip into tragedy we have just taken. Tragedy is an aesthetically conscious genre because it employs themes and conventions that give it a self-reflective undertone. Through its structure and characters, it enters dialogue on what it means to be itself. Moreover, the aesthetic consciousness of tragedy is part of the recognisable pattern of tragedy, and like a fractal, it repeats itself at smaller and smaller scales, but always reflecting the larger whole. By using Hamlet as our example to bear witness to this metaphor, we have seen that, like a fractal, tragedy’s themes spiral downward from structure, to character, and finally to being itself. The Mousetrap play allowed us to see tragedy becoming the subject of itself, repeated on a smaller scale, yet still embodying its recognisable pattern. Not only that, but we spiralled from structure into Hamlet’s psyche, where tragedy possessed him, using him as an instrument to think and speak in tragedy itself. In closing, what we discovered is not the end to this fractal metaphor nor the genre of tragedy. Instead, we learn tragedy does not resolve: it repeats, it deepens, and it thinks; maybe that is the fate of tragedy, to spiral endlessly, mirroring itself in every adaptation.

Works Cited

Abel, Lionel. Metatheatre: A New View of Dramatic Form. Hill and Wang, 1963. Internet Archive, https://archive.org/details/metatheatrenewvi0000lion/page/60/mode/2up. Accessed 29 May 2025.

Barrett, Charlie Gustafson. “Sense and Conscience: Hunting for Certainty in Hamlet.” Fictional Worlds and Philosophical Reflection, edited by Garry Hagberg, Palgrave Macmillan, 2022, pp. 349–350. SpringerLink, https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-030-73061-1_14. Accessed 29 May 2025.

Huxley, Aldous. The Doors of Perception. 1954. Faded Page, 28 Mar. 2020, https://www.fadedpage.com/books/20200328/html.php. Accessed 27 May 2025.

Liebovitch, Larry S, and Christina Shehadeh. Nonlinear Dynamics in the Life and Social Sciences. National Science Foundation, 2005. https://www.nsf.gov/pubs/2005/nsf05057/nmbs/chap5.pdf. Accessed 8 June 2025.

Natoli, Joseph. “Dimensions of Consciousness in Hamlet.” Mosaic: A Journal for the Interdisciplinary Study of Literature, vol. 19, no. 1, 1986, pp. 91–98. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/24777519. Accessed 30 May 2025.

Nietzsche, Friedrich. The Birth of Tragedy. Translated by Ian Johnston, Vancouver Island University, 2008. Project Gutenberg, https://www.gutenberg.org/files/51356/51356-h/51356-h.htm. Accessed 6 June 2025.

Shakespeare, William. Hamlet. Edited by Barbara A. Mowat and Paul Werstine, Folger Shakespeare Library, 2015. Folger Digital Texts, https://www.folgerdigitaltexts.org/html/Ham.html. Accessed 26 May 2025.

Snow, Marcus. Into the Abyss: A Study of the Mise en Abyme. 2016. PhD dissertation, London Metropolitan University. Internet Archive, https://ia600800.us.archive.org/28/items/SteinerGeorge_201504/Steiner%2C%20George%20-%20Death%20of%20Tragedy%20%28Oxford%2C%201980%29.pdf. Accessed 31 May 2025.

Steiner, George. The Death of Tragedy. Oxford UP, 1980. Internet Archive, https://ia600800.us.archive.org/28/items/SteinerGeorge_201504/Steiner%2C%20George%20-%20Death%20of%20Tragedy%20%28Oxford%2C%201980%29.pdf. Accessed 31 May 2025.